Bank of Canada (BOC) in wait-and-see mode as the oil-price shock continues to weigh.

After cutting the benchmark interest rate to 0.5% in July 2015, the Bank of Canada (BOC) has remained largely on the sidelines, as the world’s eleventh largest economy battled plunging oil prices and slowing international demand. While the outlook has improved, interest rates are expected to remain on hold until at least 2017, according to a recent poll of economists.

Snapshot of the Canadian Economy

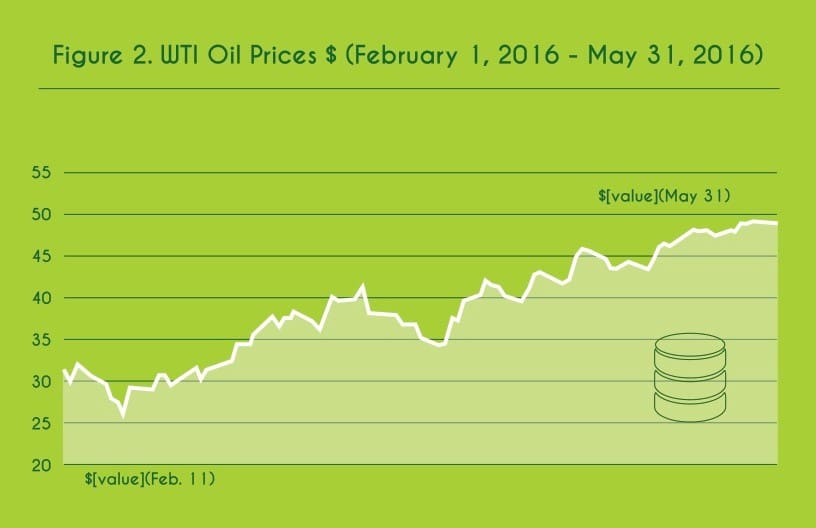

Since crawling out of recession in the third quarter of last year, Canada’s economic prospects have improved. However, growth has been choppy. The economy expanded 0.6% in January, the fastest in two-and-a-half years, before shrinking in the next two months. For the first quarter as a whole, the Canadian economy grew just 2.4%, well below forecasts calling for 2.9% (figure 1).

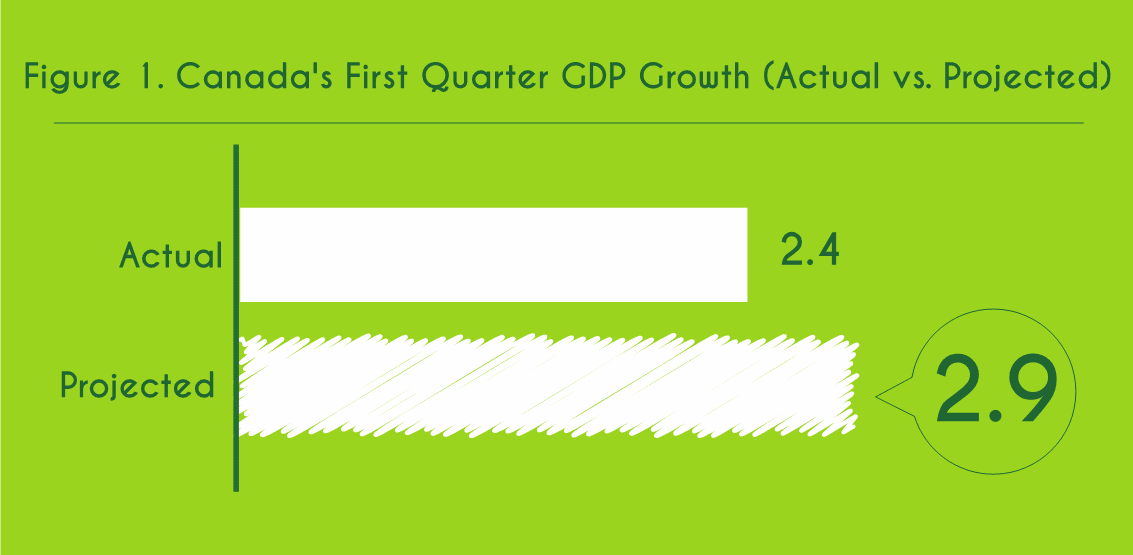

Weak business investment was one of the main factors holding back the Canadian economy in the first three months of the year.[1] Recent developments in the oil markets suggest that Canada could experience an even bigger shortfall in the second quarter. While oil prices have rebounded over 80% since February (figure 2), massive wildfires in Canada’s oil sands region has forced more than a million barrels of daily crude production offline. According to the BOC, this will shave at least 1.25 percentage points off real GDP growth in the second quarter.[2] TD Bank says it can get much worse, with recent estimates forecasting a contraction of up to 1% in the April-June period.[3]

All of this is to say that the BOC is definitely in no hurry to raise interest rates. Neither are its peers in Europe, Japan or China. With the exception of the United States, rate-hike conversations are completely off the table for most advanced industrialized economies.

Neither is Canada’s projected growth over the next two years terribly impressive. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Canadian economy is poised to grow just 1.5% this year and 1.9% next year.[4] In fact, these modest growth rates could force the BOC to wait even longer before raising interest rates again.

Implications on the Housing Market

Ultra-low interest rates have kept banks, real estate agents and mortgage specialists busy over the past 12 months, as home buyers rushed to lock-in favourable lending terms. The average commitment rate on a five-year fixed rate mortgage currently sits at 2.49%. The two-year fixed rate is as low as 2.14%.

Low interest rates not only fuel demand for housing, they increase consumers’ appetite for other goods and services. According to analysts at Canada’s largest banks, the concern isn’t low interest rates – it’s what happens when interest rates begin rising.

While we clearly demonstrated that the BOC has no intention to raise rates anytime soon, the inevitable journey back to normalcy is bound to occur at some point. It is the BOC’s hope that Canada’s economy will be strong enough to withstand gradually rising interest rates when the time comes. But with a huge portion of Canadian debt concentrated among 720,000 households – that’s 8% of the population –policymakers are concerned that families will struggle to pay off more expensive debt burdens.[5]

Soaring home prices in places like Toronto and Vancouver are certainly cause for concern, but as the OECD notes, this issue has less to do with interest rates and more to do with a lack of price-control mechanisms. Scotiabank CEO and president Brian Porter has recommended that the government consider raising down payments and increasing the mortgage rate or imposing a luxury tax on foreign buyers, which are largely responsible for the price boom in Canada’s major cities.[6]

The Broader Picture

Since Canada’s economy cannot be properly assessed in a vacuum, it must be considered in light of global economic forces. The weak global economy is already showing signs of greater fragility not just in advanced industrialized nations, but emerging economies. Japanese President Haruhiko Kuroda recently likened the current economic climate to the one that followed the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis. In a speech at the recent G7 Summit in which Canada participated, Mr. Kuroda said the global economy faces various challenges that could lead to a recession if policymakers aren’t prepared. In reality, this was the Japanese leader’s way of legitimating additional monetary easing, which he has since confirmed for September. This means Japan could lower its already negative interest rate even further and print trillions of additional yen to stimulate a stagnant economy.

The Eurozone economy faces similar challenges, as policymakers there have already tried negative interest rates. In China, the deep economic slowdown is expected to intensify over the next several years. As a result, analysts expect the People’s Bank of China to lower interest rates further in the final quarter of 2016.

The only wildcard is the US Federal Reserve, which is expected to raise rates this year, albeit at a much slower pace than previously thought. US job creation slowed to a nearly six-year low in May, the government reported on June 3. The shockingly low rate of growth virtually erased any expectation for a rate increase this summer.

Under this economic backdrop, the Bank of Canada has shown a surprisingly steady hand. The BOC’s next policy meeting is scheduled for July 13 in Ottawa.

References

[i] RBC Economics (June 3, 2016). Current Trends Update – Canada.

[ii] Craig Wong (June 5, 2016). “Fort McMurray wildfire will hurt Canadian economy: Bank of Canada.” Global News.

[iii] Greg Quinn (June 1, 2016). “’The second quarter is going to be very ugly. There’s no two ways about it’.” Financial Post.

[4] International Monetary Fund (April 2016). World Economic Outlook: Too Slow for Too Long.

[5] Romana King (June 6, 2016). “The Canadian housing market puts us all at risk.” MoneySense.

[6] Romana King (June 6, 2016). “The Canadian housing market puts us all at risk.” MoneySense.